-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

TRAINING & EVENTS

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- APPG

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

Better in theory

By Spencer Hawkins

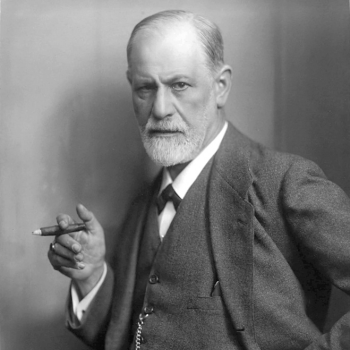

How can the translator hope to render complex theoretical concepts in another language? Spencer Hawkins looks to Freud to argue for a controversial translation approach.

The meaning of theoretical concepts such as Anlehnungstypus (Sigmund Freud’s name for the opposite of narcissism) is debated among native speakers. So how can translators hope to render them ‘accurately’ and keep the same nuances of interpretation in the target text? I would argue that ‘differential translation’ can broaden our understanding of such complex concepts.

Differential translation is my name for any context-sensitive approach to translating polysemous vocabulary. Notable published examples include translations of Machiavelli’s virtù as both ‘virtue’ and ‘skill’, Hegel’s Geist as ‘mind’ and ‘spirit’, and Heidegger’s Grund as ‘ground’ and ‘reason’. Some translators select one term or another; others alternate between translations rather than settling on one. That is what I mean by differential translation.

This translation strategy reveals points of friction between languages, exposes layers of meaning in foreign words and, at best, can provide more nuanced insight into writers’ use of concepts. It is controversial because it amounts to ‘inconsistent translation’.

Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis lament the inconsistent translation of the word nachträglich in published translations of Freud’s work1 . The word has several overlapping but related meanings for Freud; it can mean ‘after the fact’, ‘belatedly’ or simply ‘later on’. Laplanche and Pontalis consider it important to track occurrences of that word in order to understand Freud’s theory of trauma, whereas inconsistent translation makes it “impossible to trace its use”. Indeed, Freud uses the word to refer to the delay between a potentially traumatic event (in the wolfman’s case, a small child witnessing his parents having sex) and the later trigger for neurotic symptoms (like seeing a housekeeper clean the floor in a similar position to his mother during sex). However, Laplanche himself admits that Freud sometimes just means ‘later on’ when he writes nachträglich.2

Even if differential translations did impede readers from noticing Freud’s repetition of the word, and thus downplayed the concept’s relevance for the formation of trauma symptoms, they also result in more precise translations of this concept. This can be seen in Louise Adey Huish’s translation:3

It would be entirely typical behaviour if the threat of castration now took belated [nachträglich] effect.

The effectiveness of the scene has been postponed [nachträglich], and loses none of its freshness in the interval that has elapsed between the ages of 18 months and 4 years.

Huish avoids the traceability problem by putting the source word in brackets, but this would probably not satisfy Laplanche, Pontalis and their Lacanian-trained colleagues.

Context is everything

Huish was at liberty to disregard the French psychoanalysts’ wish for consistent translation of nachträglich thanks to her 21st-century publication context. Her translation of History of an Infantile Neurosis for Penguin was commissioned by Adam Phillips, who encouraged a literary approach.

In literary translation, differential translation is more than acceptable; varying one’s word choice is a matter of good style. Phillips, a writer and psychoanalyst who does not speak German, argues for this approach not because he thinks it will provide readers with a more nuanced understanding of Freud’s concepts, but simply because it will expose more of the wit, suspense and beauty of his writing – qualities readers can appreciate whether Freud’s theories are correct or not: “Freud could then be given a go as the writer he wanted to be, and is, as well as the scientist he wanted to be, and might be.” 4

In his 1918 authorised English translation, James Strachey could also translate nachträglich differentially by context, but only because Freud himself did not explicitly treat the word as a technical psychoanalytic term. Quite different is the case of the 1925 translation of Freud’s explicitly technical term Anlehnungstypus.5 In that essay, Freud argues that narcissists are capable of loving fantasy versions of themselves and others who remind them of themselves, whereas a non-narcissist (Anlehnungstypus) can love “the woman who feeds him; the man who protects him; and the succession of substitutes who take their place”.

What is a good English term for this supposedly healthy shift, made in early childhood, from a fixation on oneself to a fixation on one’s caregivers? Strachey calques the term in a footnote as “Literally, ‘leaning-on type.’” In the text itself, he translates it differentially as ‘anaclitic’ and ‘the attachment type’. ‘Anaclitic’ is a neologism, a semantically impenetrable, sublimely obscure Greek loan translation loosely mimicking the German word’s roots, while intentionally evoking the Greek grammar term ‘enclitic’. (Enclitic describes a final syllable vowel contraction in response to the next word’s vowel, as when καί becomes κ’ in κ’ἀγαθός.)

‘Attachment’ is Strachey’s far more intuitive translation, since Freud’s term refers to the normal tendency to bond with other people. However, Strachey’s footnote ends by dispelling the misimpression that the word was chosen because this type of person is capable of attachment to others: “It should be noted that the ‘attachment’ (or ‘Anlehnung’) indicated by the term is that of the sexual instincts to the ego-instincts, not of the child to its mother.”

Strachey’s second translation emphasises the way in which normal desire is linked to the early childhood experience of relying on others to fulfil one’s needs. With three terms on hand (‘leaning-on’, ‘anaclitic’ and ‘attachment’) Strachey can make Freud’s concept sound scientific yet intuitive.

Neologisms and meaning

Nearly a century later, translating for the New Penguin Freud series, John Reddick “rejected with relish and relief” Strachey’s ‘anaclitic’ as a “preposterous neologism founded on plain ignorance of Freud’s German (Anlehnung).”6 Instead of opting for further neologism or differential translation, Reddick translates the term consistently as ‘imitative type’.

In a footnote, he explains his choice: “the [related German verb sich anlehnen an] does not imply ‘attach’ or ‘attachment’; it simply means that A ‘is modeled on’, ‘is based on’, ‘follows the example of’ B”, as when past works of art or philosophy influence the next generation. The choice of ‘imitation’ suits Freud’s claim that non-narcissists take their parents as a model and seek substitutes who ‘imitate’ their characteristics.

‘Imitative type’ makes sense as a translation, but ‘imitation’ (enge Orientierung) only corresponds to the second definition of Anlehnung in the German Duden dictionary; the first definition is ‘dependence’ (das Sichstützen; Halt). ‘Dependence’ calls up both the child’s dependence on caregivers and the adult’s dependence on love from others who could very well spurn us. Narcissism, in Freud’s theory, is a reaction to unconscious terror at the thought of dependence, which prompts the libido to fasten onto a safer object of desire – the self:

It is universally known, indeed it seems self-evident to us, that anyone tormented by organic pain and dire discomfort abandons all interest in the things of the external world, except in so far as they bear on his suffering. Closer observation shows us that he also withdraws all libidinal interest from his love-objects; that so long as he suffers, he ceases loving.7

A narcissist’s pain impedes their ability to form ‘attachment’ to others, a problem which Strachey’s translation illuminates (even if this was not his declared intention).

These observations are not meant as ‘gotcha’ translation criticism;8 Strachey and Reddick both formidably capture aspects of this polysemous word’s semantic range, as the translation ‘dependent’ would have caught yet others. A differential translation of Freud’s narcissism essay might rally ‘attachment’, ‘leaning’, ‘dependence’ and ‘imitation’ for Anlehnungstypus. For instance, when Freud describes non-narcissists’ idealisation of their love objects: “For those of the dependent type, falling in love occurs when the infantile conditions of love are fulfilled.” Where he contrasts normal love with narcissism: “We are not concluding that people fall into two sharply divided groups, depending on whether they are attachment types or narcissistic types.”

Freud mentions substitution (the imitative element) when describing a child’s budding love for their mother, but only in the sense that the mother is not always the child’s caregiver: “leaning (Anlehnung) emerges in that the people involved in the feeding, care, and protection of the child become their first sexual objects, that is the mother or her substitute.” However, imitation is certainly meant when the next (cringeworthy) sentence contrasts homosexuals, ‘perverts’ and narcissists with those healthy imitative types who “choose their later love object on the model of their mother”.

At least three features can be ascribed to Freud’s concept of Anlehnungstypus: ‘normal’ folks experience libido in the form of their ego’s demands on others, that is, they experience ‘attachment’; in looking outside of themselves for love, they are vulnerable to rejection and in that sense ‘dependent’; and the presence of loving caregivers in infancy and childhood is the basis for their libido’s outward-looking orientation, which means that their choice of adult love objects ‘imitates’, or draws on, their experience of loving their caregivers in childhood. ‘Attachment’ aptly names the context; the words ‘dependence’ and ‘imitation’ are the first and second dictionary definitions of Anlehnung; and ‘anaclitic’ accomplishes the key rhetorical goal of early 20th-century Freud translation: sounding rigorously scientific. Let’s not forget the direct calque, ‘leaning-on-type’, which provides a vivid metaphor for dependence.

If differential translation were more acceptable for published translations of theoretical works, then it would be easier for translators to convey the semantic range of such immensely creative concepts. At the cost of making the term harder to trace, a differential translation of Anlehnungstypus would help show the variety of features involved in the concept.

Differential translation uncovers a complexity in Freud’s concept of normal love that makes it almost as fascinating as the narcissistic aberration. In this case, a nuanced translation could help people theorise personality disorder without feeling morally superior. If translation norms change radically enough, readers may one day be ready for differential translation to complicate more familiar terms, including ‘narcissism’ itself.

This article is based on Spencer Hawkins’ German Philosophy in English Translation published by Routledge in 2023.

Notes

1 Laplanche, J and Pontalis, JB (1973) The Language of Psycho-Analysis, trans. D Nicholson-Smith, International Psycho-Analytical Library, London, Hogarth Press, 94, 111-12

2 An Interview with Jean Laplanche by Cathy Caruth (2001); cutt.ly/twm9SHiv

3 Freud, S (2003) The Wolfman and Other Cases, trans. LA Huish, New York, Penguin Classics

4 Phillips, A (2007) ‘After Strachey: Translating Freud’. In London Review of Books, 4/10/07

5 Freud, S (1925) ‘On Narcissism: An introduction’. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: Volume XIV (1914-1916): On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other Works, XIV, London, Hogarth Press, 67-102

6 Freud, S (2003) Beyond the Pleasure Principle and Other Writings, trans. J Reddick, Penguin, xxiv

7 Ibid. 11

8 Woods, M (2013) Kafka Translated: How translators have shaped our reading of Kafka, New York, Bloomsbury Academic

Spencer Hawkins is a research fellow in Translation Studies at the University of Mainz, author of German Philosophy in English Translation (2023) and translator of Hans Blumenberg's The Laughter of the Thracian Woman (2015). Since completing his doctorate in Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan, he has taught and researched in Turkey, Austria, US and Germany.

This article is reproduced from the Winter 2023/2024 issue of The Linguist. Download the full edition here.

Filter by category

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263.