-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

TRAINING & EVENTS

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- APPG

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

Make it sing?

By Gene Hsu

Gene Hsu considers approaches to song translation and proposes a comprehensive way to discuss the process

In popular music, song translation is used to help the target audience understand the source song, but the translations are often not singable. Some are produced by translators or songwriters, while others are done by internet users. Although research in song translation is increasing, it is still rare. Most existing research discusses aspects of translation and rhyme, but few take music theory and songwriting into account.

My study of interlingual song translation1 focuses on the roles that songwriting plays in song translation. I started by doing a review of the literature. Lucile Desblache proposes that there are three main forms in interlingual translation.2 The first is when “lyrics are provided to be read/heard independently from or in conjunction with the original song or musical text”. In the second, lyrics “are intended to be sung in another language than the original language with the aim of remaining largely faithful to the message of the original language”. In the third, “they are free adaptations into another language”.3

Peter Low categorises song translation into translation, adaptation and replacement text, and proposes that “Adaptation is indeed one way of carrying songs across language borders.”4 Johan Franzon, meanwhile, proposes five choices in song translation.5 The first is to leave them untranslated. The second is “translating the lyrics but not taking the music into account” (e.g. libretto in opera). The third involves “writing new lyrics to the original music with no overt relation to the original lyrics”. The fourth is “translating the lyrics and adapting the music accordingly – sometimes to the extent that a brand-new composition is deemed necessary” (as is often seen in popular, rock and folk music).

The fifth involves “adapting the translation to the original music”, which is similar to Desblache’s second or third form. A Cantonese version of ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ from the musical Les Misérables uses the third method while a Mandarin version uses the fourth with the music unadapted. The lyrics of both versions are adapted to the original music:

It is important to distinguish between song lyrics and song text, though the two are easily confused. Lyrics are ‘singable’ while song text may not be; in other words, song lyrics serve for singing purposes and can be regarded as ‘song text’ or a subcategory of ‘song text’.

The translation approach will depend on the reason for producing the target text – whether to create song lyrics for the purpose of singing in the target language or to create a written translation without the purpose of singing. In the former, the meaning of the target lyrics will not be the same as that of the source lyrics. The original messages can be reduced, adapted, rewritten or abandoned. Moreover, Desblache states that music has “inspired new forms of translation” in recent decades. This includes localising songs, where the new lyrics vary according to the target culture, audience, language and social milieu.

The purposes of translation

New lyrics can be localised to reflect social and current affairs. The Cantonese version of ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ was first posted on Facebook by the campaign group ‘Occupy Central with Love and Peace’ in May 2014, as discontent was growing in Hong Kong. In light of this societal background, which led to the ‘Umbrella Revolution’ street protests, it has been presumed that the translation was produced for use in the protests. The Cantonese lyrics support this assumption (see table, above).

A singable target song can be regarded as a localised song if the majority of the target lyrics bear different meaning and words from the source song lyrics. This is acceptable if the aim is to create new singable lyrics that have no relation to the source lyrics.

When the purpose is to preserve the meaning without considering singability, 100% must be faithfully translated. This can help target audiences to understand the ideas and messages of the original song. For instance, in opera, singers rarely perform in the target language and libretto is used instead. Back translation or literal translation of lyrics is common among ‘fan translation’ for the same reason. In films or TV series, interlingual subtitling is often used to help viewers understand the dialogue. When a character is singing, or a song plays in the background, the lyrics are also translated but unsingable.

The assessment of categories of song translation should be carried out using specific criteria. Where Low, Franzon and Desblache refer to a ‘majority’ of text being of a certain type (e.g. differing in meaning to the original), that majority should be defined with a scale when target and source lyrics are compared.

Accordingly, I propose that a song text can be regarded as ‘translated’ if the singable target lyrics retain 91% or more of the original meaning of the source lyrics. It can be regarded as ‘adapted’ if the scale decreases to 51-90%, and as ‘rewritten’ when the percentage reaches 11-50%. Finally, it can be considered ‘brand new’ when it retains 10% or less of the meaning.

Producing singable lyrics

To produce singable target lyrics, Low suggests translators should pay attention to vowels in order to produce songs that rhyme.6 Thus, songwriting can play a pivotal role in song translation, taking song structure, melody, rhythm and rhyme into account.

Songwriters can adjust the order of the words in the target lyrics to adapt the syllables to the music, so that the lyrics can be both singable by singers and listenable to by target audiences. This can help develop lyrics that are not only “possible to sing”, but also “suitable for singing” and “easy to sing”, says Franzon.7 New singable lyrics can be either faithful or not to the original meaning.

Furthermore, when songwriting, music theory and practice are applied to song translation, dubbing or covers, the target lyrics imbue a high aesthetic appreciation of music. For instance, 流れ星 (‘Meteor’),8 a Japanese version of the Mandarin pop song 小幸運 (‘Little Happiness’), sung by Marina Araki, uses new lyrics. They bear little resemblance to the original lyrics, but carry the same sense of a relationship ending and similar emotions of loss, confusion and sadness.

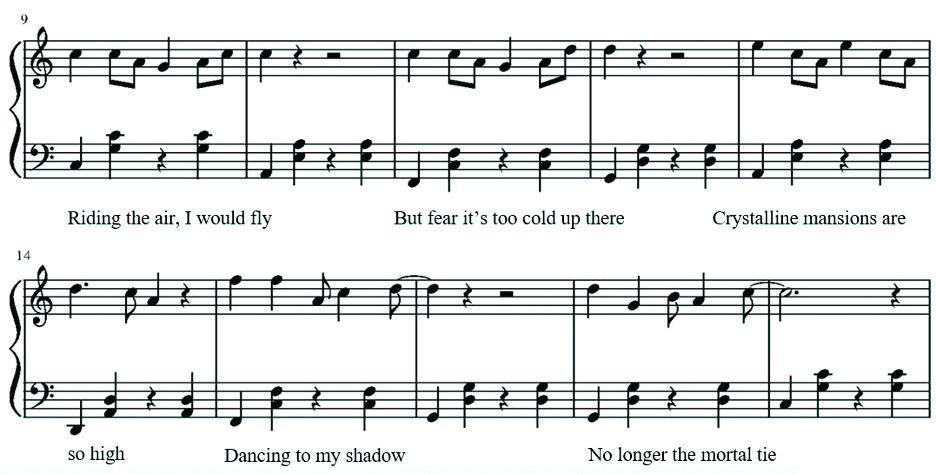

My English version of the Mandarin song 但願人長久 (‘Prelude to Water Melody’) composed by Vincent Liang has singable lyrics in English. I paid attention not only to rhyme and vowel sounds, but also to musical elements, including song structure and poeticity, to improve singability. For instance, I adjusted the word order from 唯恐瓊樓玉宇, 高處不勝寒 (lit. ‘But fear that the crystalline mansions are so high and too cold there’) to ‘But fear it is too cold up there/ Crystalline mansions are so high’. In this way, the lyrics are adapted to the music:

In verse 1, I adapted the number of syllables to the music. For instance, I omitted ‘[I] do not know that’ from the lyric 不知天上宮闕, 今夕是何年 (lit. ‘[I] do not know that in the celestial palace, which year it is on this day?’),9 because audiences can understand it is a question without that phrase. I also ensured the lines rhyme: ‘In the celestial palace up so high/ What day tonight goes by?’ Previous poetic translations did not aim at singability, though they preserved the meaning and main idea of the original poem.10

Singability, understandability and listenability should be assessed through assessment criteria that help to identify and categorise target lyrics. This will help a translator, songwriter or singer better understand approaches to song translation and select appropriate methods. Thus, to produce singable songs in a language other than the one in which the source was produced, it is important to take musical analysis and performing arts into account.

Notes

1 Hsu, G (2024) ‘Music and Translation – A Study of “Singability” of Chinese Versions of the English Song “Do You Hear the People Sing” in the Musical “Les Misérables”’; and ‘Interpreting and Translating Music from Classical Chinese Poetry into Modern English Song – A Study Case of SU Shih’s “Prelude to Water Melody”‘. Unpublished research papers

2 Desblache, L (2018) ‘Music Translation’. In Washbourne, K and Van Wyke, B, The Routledge Handbook of Literary Translation, Routledge

3 Desblache, L (2018) ‘Translation of Music’. In Chan, S, An Encyclopedia of Practical Translation and Interpreting, Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 297-324

4 Low, P (2013) ‘When Songs Cross Language Borders’. In The Translator, 19,2, 229-44

5 Franzon, J (2008) ‘Choices in Song Translation’. In The Translator, 14,2, 373-99

6 Low, P (2008) ‘Translating Songs That Rhyme’. In Perspectives, 16,1-2, 1-20

7 Franzon, J (2015) ‘Three Dimensions of Singability. An approach to subtitled and sung translations’. In Proto, T, Canettieri, P and Valenti, G, Text and Tune. On the association of music and lyrics in sung verse, Bern: Peter Lang, 333-46

8 林さん(2017) ‘流れ星 - 荒木毬菜’; jpmarumaru.com/tw/JPSongPlay-6484.html

9 何年 literally means ‘which year’, but because Chinese is paratactic, it is generic and could also mean ‘which festival/day/moment/night’.

10 Xie, K (2016) ‘四位英文大師翻譯蘇軾的"水調歌頭.明月幾時有’; https://cutt.ly/Nee6e4KI

Gene Hsu (legal name Jingqiao Xu) focuses on music and translation/languages in her interdisciplinary and intercultural research, drawing attention to song analysis, covers and songwriting when studying song translation. She has presented her papers at global academic conferences.

This article is reproduced from the Summer 2024 issue of The Linguist. Download the full edition here.

Filter by category

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263.