-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

TRAINING & EVENTS

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- APPG

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

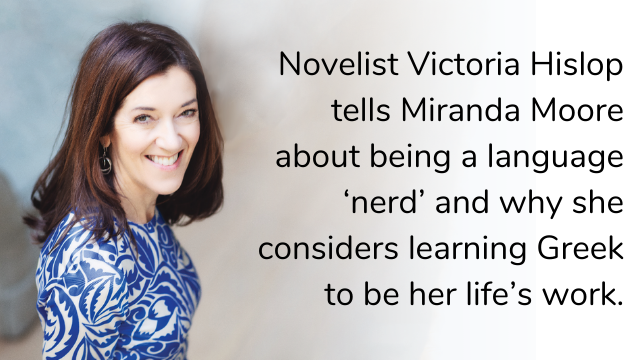

From geek to Greek

Victoria Hislop’s love of Greece runs through her eight novels – every one of them set in the country. So much so that she was awarded honorary Greek citizenship in July for promoting the nation’s history and traditions. Though I knew of her reputation as a dedicated hellenophile, I was less aware of her passion for languages when we spoke in October. I discovered a bestselling novelist who describes her life’s work as the study of Greek – who grew up speaking French with the English girl next door and still plays make-believe with her grown-up son (the actor Will Hislop) to teach him Greek. (“He could get a book if he wanted to, but this is a fun thing.”)

How her love of Greece began has been well-documented: as a 17-year-old with little experience of trips abroad, she was taken to Greece by her recently divorced mother Mary, and instantly fell in love with the place. Coming from a fairly “typical” family in Kent, who holidayed on the South Coast and were not particularly interested in languages, it was all very exotic. Though she returned to Greece often as she embarked on adult life, she didn’t have much of a connection with Greek until much later. “At the time, the language seemed so completely alien because of the alphabet. A privately educated person might have had fun transliterating, but I hadn’t done Ancient Greek at school. I didn’t think there was any possibility of speaking it.”

This is slightly surprising when you consider Hislop’s early aptitude for languages. She choose to speak not just French with her friend, Angela, on the walk to school, but also German and Spanish when their grammar school introduced those languages. “It sounds so funny now but we absolutely did this, and we walked to school and back every day for a decade,” she says. One of them was always top of the class in languages. “We were competitive in a nice, friendly way, because we egged each other on.”

A “ghastly” French exchange aged 11 (“I was far too young”) almost put her off going to France. She describes the environment as “very alien”. “I was in France, with smells of garlic, which I’d never even tasted. I’m talking 1971. Spaghetti only came out of tins in those days! Culturally, we weren’t European in any way in Britain.” But the experience did not affect her enjoyment of the language, which she spoke with her Parisian step-father. “I absolutely loved speaking French. For many years, I had in-house French conversation and I really grabbed that opportunity.”

She went on to study English at Oxford, where she met her husband, Private Eye Editor Ian Hislop. After a career in publishing and public relations she became a journalist, writing her first novel, The Island, in her 40s. Inspired by a trip to the former leper colony on Spinalonga, the book was an immediate bestseller and has since been translated into more than 30 languages. The sequel, One August Night, published in October, explores the tragic events that follow the colony’s closure.

In 2010, The Island was made into a successful TV series in Greece. Hislop was heavily involved in the production, and even had a walk-on part, along with Ian. She sees a correlation between acting and language learning: “Language to me is a lot about being prepared to act, because you have to act – in verbal terms – to start with. You’re acting being French or Spanish or Greek.” With Will, they pretend he is a Greek man, and he is learning the language in this way. Both children speak French and Emily “thinks, lives, breathes Spanish”.

In a sense, writing fiction is also a form of mimicry, reflecting how people speak, react to situations and understand events. Hislop’s novels have always been meticulously researched, even before she was able to understand the language, but she admits: “I don’t think you can get beyond a certain point of understanding a country or the people, or the way they live or communicate, unless you can speak the language.” There were two “very specific” events that began her journey with Greek. The first came after The Island was translated into the language. It was an instant hit and a nationwide book tour followed. “At the first presentation I had an interpreter and I couldn’t stand it because everything I said took twice as long in Greek. It seemed to take hours,” she says.

“It’s hard to explain – I was kind of angry because I felt foolish, like a three-year-old who’s being patronised. It was a great incentive.” She returned to London and began intensive 1-to-1 lessons. “My teacher asked ‘What’s your motivation?’ I said ‘In three months’ time I want to be able to conduct an interview about my work.’ So he kind of swallowed and we got on with it.”

Soon after, she was introduced to Manoli, an elderly Cretan man who had survived leprosy. Her desire to connect with him became another powerful motivation. “We had a real connection and I dreamt of being able to communicate with him directly,” she says. “There was always a time limit because he was 82, he had problems with his lungs. I knew I didn’t have 10 years. If you’ve got a real target with language learning that helps.”

With its many declensions and cases, and the different alphabet, Greek is not an ‘easy’ language for English speakers. But it’s not all the hard climb, says Hislop. “You kind of go up a steep slope and then suddenly you think ‘Wow, I can understand people’, and then there’s the next steep hill and you’re on a plateau where you can have a conversation with somebody.”

The current challenge is writing in Greek, as she decided to write the first draft of a new children’s version of The Island in the language. It felt right because “my vocabulary is probably like an eight-year-old’s and that’s the audience for the book,” she says. Due for publication next year, the book will include some new, younger characters.

Though Hislop will probably never write an adult novel in Greek, knowledge of the language does inform the way she writes. “I’m not writing as though an English person were speaking, because the Greeks do express themselves differently. I don’t know whether that comes across to the English reader, and it’s not every time a character speaks, but I hope sometimes I get it,” she says.

“I don’t think there’s any such thing as direct translation because people do express themselves differently in other languages, and words tend to have different nuances. I explore that as much as I can when I’m writing my novels.” Instinctively Hislop feels that she, too, expresses herself differently in the other language. In French, she doesn’t speak ‘in translation’, and she is getting to that point in Greek too (which she speaks with a French accent).

When it comes to the translation of her books, her knowledge of European languages gives her an interesting insight. Occasionally a fan who has read her work in another language asks her about something that she doesn’t remember writing. “I can go and check that the translator hasn’t changed anything, and sometimes they have. It is probably quite annoying for them,” she adds.

Despite selling millions of copies around the world, Hislop doesn’t consider herself to have many ambitions – except with Greek. “That’s where I can make big improvements. It’s still a very exciting learning curve.” A generous conversationalist, she asks about my linguistic experiences as the interview comes to an end, and seems genuinely interested when I talk about learning Spanish in Mexico. Excited by the many options for TV viewing in Spanish, she recommends a few telenovelas, trying to remember the ones Emily has most enjoyed. Her parting words to me? “Languages: they’re the most exciting thing that your brain can undertake, I reckon.”

Victoria Hislop’s latest novel, One August Night, is published by Headline Books.

Filter by category

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263.