-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

TRAINING & EVENTS

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- APPG

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

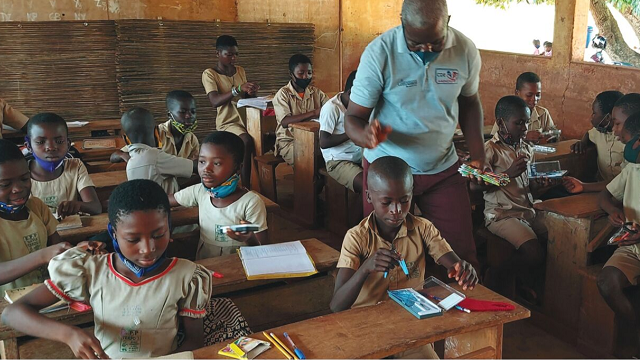

A class act for Togo

By Lucy Makepeace

Lucy Makepeace travels to the West African nation to help improve the way Ewe-speaking pupils are taught French

Lucy Makepeace travels to the West African nation to help improve the way Ewe-speaking pupils are taught French

When I went to Senegal on a humanitarian mission in 2018, the level of poverty among the street children and communities I worked with was heartbreaking but sadly not unexpected. What really shocked me was that citizens were expected to speak French like French people to pass examinations, interact with the authorities, do basic administrative tasks and get good jobs, yet the provisions for French teaching were inadequate. Returning to francophone Africa the following year, I found a similar situation in other countries.

I spent three months living in a village in Togo and volunteering full-time at a local primary school with the charity Assemblessan-Assemblessan. More than 40 languages are spoken by the 8.5 million citizens of this small West African nation, but the education system requires a level of French that is not currently attainable for most children. Although there has been a recent push to promote early education in the main local languages (Ewe in the South and Kabiye in the North), exams and lessons are generally conducted exclusively in French. However, some students cannot even hold a simple conversation in the language. I found that children fail in areas such as maths and science, not because they haven’t mastered the academic principles but because they do not understand the wording of the questions.

There is currently little research available on Togo’s linguistic composition, but the multilingual nature of my fiancé’s family is fairly typical: with the maternal grandmother they speak Moba; with the dad they speak Gourma; since they live in the capital city of Lomé they speak Ewe when people come to the house; and in their professional lives they speak French, which is used as a lingua franca across Togo’s many ethnic groups.

In September, I returned to Togo to work closely with the school in Davie-Tekpo, 30 km from Lomé, while also developing my business, The Language Agency. The 800 pupils at the school have no access to reading books or media; they do not speak French outside the classroom, as the common language is Ewe and most of their parents speak little to no French. As a result, some pupils have had to retake classes, while others drop out before completing primary.

Space has also been a big problem. With one teacher per 100 pupils there was no time to correct work, including errors in the French, which made it hard for pupils to progress. More importantly, despite the teachers doing a stellar job of controlling the classroom, it was almost impossible for children at the back to hear. Extra teachers were available but there were not enough classrooms. Thanks to crowdfunding, and an incredible construction effort from the entire village, we were able to build three new classrooms. This means that classes have been split in half, which has made a big difference.

It is still important to fill the gaps in teaching in order to improve pupils’ understanding of French, thereby increasing their chance of success in terms of state exams and job opportunities. Every Tuesday, I get up at the crack of dawn to go to the school (I have to wait for it to be light enough to drive). My first task is to conduct the daily mental maths test. At first, I didn’t want to do this as I was faced by a sea of concerned faces, and could hear mutterings in Ewe: “What did Miss say?” Simple questions would throw them, for example: Si une banane coute 50 CFA, combien faudrait-il pour acheter un régime de 10 bananes? (‘If one banana costs 50 CFA, how much would you need to buy a bunch of 10 bananas?’) Understanding the word ‘bunch’ is not essential to the task, but when I put this question to my students the majority spent the entire time trying to work out what régime could mean and therefore failed to give an answer.

I now try to reword any questions that cause difficulties, and at the end of the test we discuss strategies for understanding and solving the maths problem without necessarily understanding every word. This ‘concession’ isn’t a luxury they will have in the real exam, but we can at least provide them with methods that will help them overcome linguistic barriers to completing the test.

Pupils still struggle with my European accent, but both the teacher and I believe that getting used to it will help them in the long run. In job interviews, for example, ‘good’ (mainland France) French is preferred to French spoken in a Togolese accent with local idioms. This is a shame as pupils do not have adequate means of developing their French in this way. They have often never come into contact with anyone from France, while French TV channels are a luxury that few can afford.

To improve their outlook, I plan to implement a spelling programme with spelling tests (not currently part of the curriculum), carry out dictations, go through grammar and vocabulary with French as a Foreign Language activities, and mark pupils’ written French (something overstretched staff have been unable to do). The smaller class sizes enabled by the new classrooms, and additional teaching time from volunteers, will free up teachers’ time so they are also able to do this work.

The dream is to have enough books to give children reading homework, like I had growing up in the UK. However, the immediate priority is providing the bare minimum. With a £200 crowdfunding donation, I put together a school kit for the 55 pupils in my class, including items such as a pencil case, protractor, set square, ruler, rubber, pens and crayons. With the rest of the money we bought textbooks for students who didn’t have them. Since pupils who do not have the required school materials are often sent home, I hope

to do this every year so that all the local children can access education.

With money collected through fundraising, support from Assemblessan-Assemblessan and the CIOL Nick Bowen Award, we are also converting one of the storerooms into a library, giving children access to written French for the first time. The goal is to create a space where pupils can read and be introduced to languages, books and DVDs. This will undoubtedly improve their spelling and understanding of French, and support their education in all subject areas, with access to fiction and non-fiction books, encyclopaedias and dictionaries.

We hope to run a weekly ‘open library’ session where pupils can come to read, ask questions and practise their language. To support the children fully, I am studying Ewe and I am committed to improving my skills in the language. The teachers use Ewe to communicate with parents and pupils when necessary, and although I will continue to use French as the main language of instruction, I will also use Ewe when comprehension is impaired.

A school is at the centre of a community and the involvement of parents is fundamental. It is important that our work benefits the whole school community, and when pandemic restrictions are lifted we hope to organise regular film evenings using a donated laptop, the charity’s projector and the electricity supply installed thanks to the generosity of others. This means the whole village will soon to be able to come and watch films in French, German and English for the first time.

I hope that once the pandemic is over more language students and professionals will seize the life-changing opportunity to use their language skills for the greater good. I think this is the reason that a lot of us choose to pursue languages. I will never be able to give sufficient thanks to the incredible teachers, inspirational children, and resilient and welcoming community. Although I find teaching in the sweltering heat a lot more demanding than translating in my air-conditioned home office, I come home every week with a smile on my face and renewed motivation. Akpe kaka! Merci beaucoup! Thanks a lot!

If you are interested in working with local communities in Togo, contact assemblessanassemblessan@gmail.com or visit cutt.ly/Davie-Tekpo to donate to the project.

Filter by category

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263.